Sugar Bee Sets Sights on Mushroom Markets

Jutting out of dewy, straw-filled bags are gnarly creations in rainbow colors that look more like sea creatures than the blanched, lifeless mushrooms most Americans are accustomed to on supermarket shelves. But the oyster mushroom — pleurotus ostreatus — is in high demand from creative culinary types and adventurous eaters. And the crops coming from Sugar Bee Farm are nothing short of edible works of art.

The name Sugar Bee might make you think of a familiar sweet, golden, oozy substance, but the choice crop at Sugar Bee Farm is spongy, delicate oyster mushrooms. Sarah Wisniewski and Dave Grow own and operate this year-round farm — the only devoted mushroom farm in Milwaukee — producing eight varieties. They plan to add bees and honey to their repertoire next.

With the help of a USDA Farm Service Agency (FSA) micro loan, Wisniewski and Grow moved into a warehouse space on July 1 and within five weeks had their first harvest. Sugar Bee is the latest addition to Milwaukee’s Green Corridor running along 6th Street from Howard to College Avenue on Milwaukee’s South Side.

A tour of the farm began outside peering into a pile of straw. Often the most tedious step in the process, shredded straw is the substrate or growing medium for the mushrooms.

Wisniewski and Grow soak bags of straw in a limestone bath in the inoculation room to elevate the PH and kill off competing microorganisms. This pasteurization process gives the seed a head start to spawn the mycelium, a milky coating encasing the straw, that is the vegetative part of the fungus.

In the incubation room, the damp, straw-filled bags are primed for mycelium to prosper in a 75-degree room for two to three weeks. A thick, moist air hangs in the dark room, heated partially by the process of mycelium breaking down the straw.

Then, the bags are lined up neatly on wooden shelves in the fruiting room. With strands of neon lights draped from the shelves and humid air that sticks to your pores, it feels like a college dorm room, the portly straw bags mimicking kegs of beer. The bags get 12 hours of light every day and added oxygen flow causes the mushrooms to burgeon out of tiny holes 72 hours later. Sugar Bee’s pink, yellow, white, gold, and brown mushrooms look more like flowers than fungi.

“Actually, the part that you eat is the reproductive organs of the mushroom,” says Wisniewski. “Think about that next time you eat a mushroom,” jokes Grow.

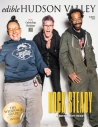

The two play off each other like Abbott and Costello, but with an intricate grasp of science and food systems; it’s obvious they’ve been working seven days a week, 12 hours a day, in the world of mushrooms.

Grow, a native New Yorker, taught English overseas and worked on farms worldwide studying food systems. He met Wisniewski working on a farm in Milwaukee and decided to throw himself into it. Aside from the befitting surname, his beard outlines an ear-to-ear grin and he is clad in flannel and rubber boots. This guy looks like he was made to be a farmer.

Wisniewski has her master’s degree in science and has worked at local urban farms. When she met her “mushroom guru” Rafter Sass, an agroecologist from Vermont, she developed her love affair with edible fungi and mycelium. She began experimenting and learning as much as she could before she and Grow decided to create Sugar Bee. Wisniewski is soft-spoken, but incredibly knowledgeable and passionate about her life’s calling.

“Mushrooms externally digest food — they are the planet’s recycler, producing enzymes and acids that break down and absorb nutrients while also leaving nutrients behind,” explains Wisniewski. “And they have so many nutritional benefits. They are high in Vitamin D, potassium and B vitamins.”

Sugar Bee is delivering 50 pounds a week to three restaurant customers right now, although Wisniewski and Grow are hoping to produce a few hundred pounds a week to be fully financially sustainable. “The ability and capacity is there, but we’re still working out the kinks,” says Grow. There is currently room for 800 bags and another untapped room has space for 600 more.

AP Bar and Kitchen and Crazy Water, both in Walker’s Point, have been experimenting with four different varieties of Sugar Bee mushrooms in dishes like red wine risotto with mushrooms and mascarpone, and mushrooms with madeira cream sauce on toast points. The pink mushrooms are woody, meaty and slightly pungent, pairing well with bacon and prosciutto. Whereas the golden mushrooms have a buttery, citrusy tang to them, with hints of anise. The poju variety has a nutty flavor, and the grey mushrooms are firm and earthy with a mild sweetness.

Sugar Bee hopes to expand to more restaurants, health food stores, and farmers markets very soon. While they look toward expanding production and holding workshops, they agree that maintaining the connection to chefs using their products is of the most importance.

Wisniewski and Grow employ traditional mushroom farming techniques, but are committed to incorporating sustainable practices. They donate leftover mushroom compost to schools and community gardens, and have been collecting sawdust from Flux Design and coffee grinds from Collectivo to use in their farming.

The reaction from the chefs and the ability to create that 24-hour farm-to-table connection is by far the most gratifying aspect of their work, the urban farmers say.

“You never hear about Milwaukee as being a food town,” Grow admits. “But when you get here, it really is. You walk into restaurants and see chalkboards listing where they get their food and the local farms they support. The worst part is that not enough people know about it, but we are proud to contribute to it.”